1. Double Agents in the IRA. I recently came across an excellent article by Matthew Teague in The Atlantic about the British counterintelligence program and the IRA. It’s from 2006, but still engrossing.

2. Restoring Journalism. Maureen Tkacik talks about her life as a journalist, the nothing-based economy, and the future of journalism:

If journalism’s more vital traditions of investigating corruption and synthesizing complex topics are going to be restored, it will never be at the expense of the personal, the sexual, the venal, or the sensational, but rather through mastering the kind of storytelling that understands that none of those things exists in a vacuum. For instance, perhaps the latest political sex scandal is not simply another installment of the unrelenting narcissism and sense of invincibility of people in power. Most of the journalists writing about it have—as we all do—some understanding of the internal conflicts that lead to personal failure. By humanizing journalism, we maybe can begin to develop a mutual trust between reader and writer that would benefit both.

What I’m talking about is, of course, a lot easier to do with the creative liberties afforded a blog—one’s humanity is inescapable when one commits to blogging all day for a living.

The piece is long, and worth every word. (H/t to John Cantwell.)

3. The Papacy, Blumenthal, and Now Goldman Sachs. The New York Times took on Goldman Sachs earlier this week with a look at the perfectly legal but unsavory practices it uses to make money:

Transactions entered into as the mortgage market fizzled may turn out to have been perfectly legal. Nevertheless, they have raised concerns among investors and analysts about the extent to which a variety of Wall Street firms put their own interests ahead of their clients’.

“Now it’s all about the score. Just make the score, do the deal. Move on to the next one. That’s the trader culture,” said Cornelius Hurley, director of the Morin Center for Banking and Financial Law at Boston University and former counsel to the Federal Reserve Board. “Their business model has completely blurred the difference between executing trades on behalf of customers versus executing trades for themselves. It’s a huge problem.”

4. Erroneous Assumptions. Matt Yglesias concisely summarizes what left-leaning advocates of bipartisanship have found time and again:

Oftentimes people reach the conclusions that conservatives might support this or that by the erroneous method of pretending that conservatives believe in the stated reasons for their policy positions. It seems to me that private views of wonks aside in practice the conservative political movement simply opposes anything that would increase government revenue and/or be bad for rich people.

5. The Tyranny of New York (cont). Continued from last week, many voices around the interwebs weighed in on the conversation started by Conor Friedersdorf on the tyranny of New York in media and culture. There’s a lot of good pieces to read on this — but the 2 I will recommend are this response in the New Yorker by Amy Davidson and this follow-up by Friedersdorf himself. Davidson, as an aside mentions an E. B. White essay “Here Is New York” that I now need to read:

(Friedersdorf mentions “living vicariously through” E. B. White, who once wrote that there were three New Yorks, that of the native, the commuter, and the newcomer from smaller American places, and that “Of these trembling cities the greatest is the last—the city of final destination, the city that is a goal…Commuters give the city its tidal restlessness, natives give it solidity and continuity, but the settlers give it passion.” But I’ve never really bought that, as matchless as many of White’s descriptions of the city are, maybe because, as a native, I feel no shortage of passion, and don’t much like being called solid. And, again, for many of the most interesting newcomers, this is an entry point to America, not the “final destination.”)

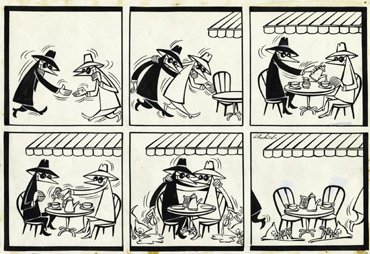

[Image by me.]