[digg-reddit-me]David Brooks did a great job today of describing the type of individual our current Supreme Court confirmation process tends to reward (to paraphrase):

A person whose career has dovetailed with the incentives presented by the confirmation system, a system that punishes creativity and rewards caginess, and who therefore we are forced to construct arguments based on speculation because they have been too careful to let their actual positions leak out.

Brooks locates this type of individual — as is his wont (see for eg. bobos) — in a general sociological group:

About a decade ago, one began to notice a profusion of Organization Kids at elite college campuses. These were bright students who had been formed by the meritocratic system placed in front of them. They had great grades, perfect teacher recommendations, broad extracurricular interests, admirable self-confidence and winning personalities.

If they had any flaw, it was that they often had a professional and strategic attitude toward life. They were not intellectual risk-takers. They regarded professors as bosses to be pleased rather than authorities to be challenged. As one admissions director told me at the time, they were prudential rather than poetic.

Brooks sees this as a flaw in his evaluation of Elena Kagan:

Kagan has apparently wanted to be a judge or justice since adolescence (she posed in judicial robes for her high school yearbook). There was a brief period, in her early 20s, when she expressed opinions on legal and political matters. But that seems to have ended pretty quickly…

But I was struck by the similarity of David Brooks’s evaluation of Elena Kagan now and Dahlia Lithwick’s evaluation of John Roberts when he was nominated:

I knew guys like [John Roberts] in college and at law school; we all knew guys like him. These were the guys who were certain, by age 19, that they couldn’t smoke pot, or date trampy girls, or throw up off the top of the school clock tower because it would impair their confirmation chances. They would have done all these things, but for the possibility of being carved out of the history books for it…

My sense that Roberts has been preparing for next month’s confirmation hearings his whole life was shored up by a glance at the new memos released by the Library of Congress yesterday. As early as 1985, Roberts was fretting about how federal government records disclosed to Congress before confirmation hearings could tank a nomination.

Roberts was widely seen to have been very “careful” and “cautious” throughout his life — intellectually and otherwise. Yet David Brooks had a different reaction to Roberts nomination:

Roberts nomination, how do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

Less important than this minor bit of hypocrisy (which Bill Scher for the Huffington Post mines for all it’s worth) — or perhaps partisan blindness — on the part of David Brooks (and haven’t we all been there?) — is the substance of his critique. Brooks never quite connects the dots — but seems on the verge of making a profound point.

There seems to be a connection between the personality type of Kagan and Roberts — the type of cautious, establishment-minded personality rewarded by our current nomination process — and the tendency of this type of person to defer to the highest authority figure in the American psyche, the President of the United States. In Roberts and Alito, we have 2 of Brooks’s Organization Kids who also happen to be 2 of the most pro-presidentialist Supreme Court justices in history. Though Kagan’s views on this aren’t clear — as she has made some comments indicating an expansive view of executive power only in the context of discussing the views of others — we do know that she felt the Bush administration went too far, unlike Roberts and Alito.

Though I would have preferred a justice more wary of executive power, for me personally, this concern is not enough to give me reason to oppose Kagan’s nomination and appointment. I do want to know more about Kagan’s views on this — to see whether and to what degree she conforms to Glenn Greenwald’s fears (which are, as it should go without saying regarding Greenwald, hyperbolic). Lawrence Lessig has pushed back convincingly against Greenwald on this issue — and of course, Greenwald responded by going ad hominem.

Both Greenwald’s and Brook’s critique ignores the structural element to this pick as neither addresses the degree to which our current confirmation process tends to reward cautious people whose public views are somewhat ambiguous but who are close enough to those in the executive branch that the President nominating them trusts them. The type of person who would meet these criteria would not tend to be the strongest supporters of the Court as a check on executive power. Even aside from the generational category of “Organization Kids,” this would tend to place people deferential to presidential authority into the Supreme Court.

—–

Also interesting: Ezra Klein posits a better analogue than John Roberts to understand the Kagan pick is Barack Obama himself:

When Obama announced Kagan’s nomination, he praised “her temperament, her openness to a broad array of viewpoints; her habit, to borrow a phrase from Justice Stevens, ‘of understanding before disagreeing’; her fair-mindedness and skill as a consensus-builder.” This sentence echoes countless assessments of Obama himself.

Obama is cool. He makes a show of processing the other side’s viewpoint. He’s more interested in the fruits of consensus than the clarification of conflict. In fact, just as Kagan is praised for giving conservative scholars a hearing at Harvard’s Law School, Obama was praised for giving conservative scholars a hearing on the Harvard Law Review. “The things that frustrate people about Obama will frustrate people about Kagan,” says one prominent Democrat who’s worked with both of them.

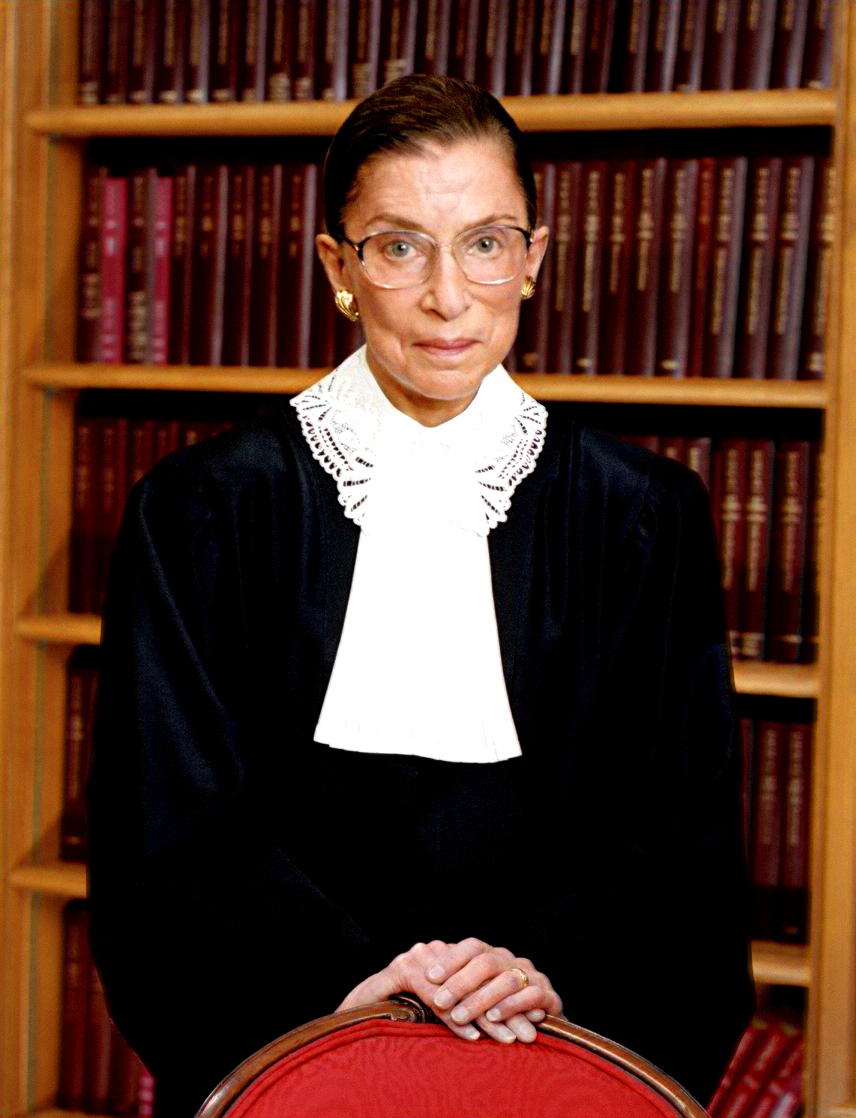

[Image by the Harvard Law Review licensed under Creative Commons.]