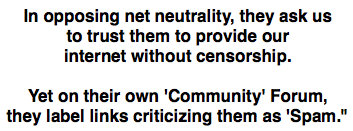

[digg-reddit-me]AT&T has emerged as the main opponent of net neutrality – while it has tried to paint Google as its main proponent (a surprising move given Google’s popularity.)

Yet, as AT&T now embraces the language of the free market and cloaks itself in libertarian rhetoric about government interference and regulation, it’s worth considering its history. AT&T’s business model is and has always been about manipulating the government for its private advantage. (In this it isn’t much different than most corporations – except in its spectacular success.) According to Adam D. Thierer (whose name will come up later), under company president Theodore Vail during the early 20th century, AT&T’s main goals were:

the elimination of competitors, the befriending of policymakers and regulators, and the expansion of telephone service to the general public.

By 1913, as AT&T had bought up many competitors and driven many smaller companies out of business in local phone service and taken a dominant position in long-distance calling, the Justice Department became concerned that AT&T was becoming a monopoly to the detriment of competition. At this point, AT&T voluntarily entered into the Kingsbury Commitment to avoid the otherwise inevitable regulation – agreeing to withdraw from certain markets (divesting itself from Western Union which it had just bought for example) and to stop its war on smaller local calling companies. They secured their advantage though and were able to continue to solidify its lucrative effectively monopolistic position in long-distance.

As the company continued to solidify its position, it was wary of inciting government efforts to break up its monopoly and so avoided typical practices of monopolies such as raising prices quickly. But during World War I, the company was nationalized and controlled by the Postmaster General. AT&T, now safe from monopoly concerns, immediately lobbied the postmaster general to allow it to raise rates significantly, which under normal circumstances would have triggered concern about monopolistic abuse of power. But, as a government entity during a time of war, AT&T was given this allowance: AT&T raised its rates 20% in the first half year under government control. In addition, the government decided to compensate the company with $13 million “to cover any losses they may have incurred, despite the fact that none were evident,” as Thierer points out.

Subsequently, AT&T began lobbying for government regulation of long-distance rates to solidify their advantage as the de facto monopoly of the long-distance. They succeeded in return for their promise to extend universal telephone coverage. This bargain with the government as well as AT&T’s prestige and government contracts gave it great pull with the FCC such that the FCC protected it. Thierer again:

Beside its powers to regulate rates to ensure they were “just and reasonable,” the FCC was also given the power to restrict entry into the marketplace. Potential competitors were, and still are required to obtain from the FCC a “certificate of public convenience and necessity.” The intent of the licensing process was again to prevent “wasteful duplication” and “unneeded competition.”

…[The FCC would] use its power in favor of AT&T when potential competitors threatened the firm’s hegemony.

Thierer’s history ends here. But AT&T never stopped lobbying the government for favors. In the late 1950s, as it attempted to block any competitors from even improving its product. AT&T owned all devices connected to its network, merely licensing phones to its customers – and maintained the right to block the sale of any “unauthorized foreign attachments” and terminate service to anyone who used them.

AT&T continued to fight for special government favors in the 1980s and 1990s – as Dick Martin, former head of public relations for AT&T and author of Tough Calls: AT&T and the Hard Lessons Learned from the Telecom Wars, explained in an email interview with me – attempting to block competitors from getting into long distance as well as lobbying on more esoteric issues, as they attempted to reduce “access charges (i.e., the per-minute rate the local phone companies charge to originate or complete a long distance call) [and] the cost of unbundled network elements (i.e., what local phone companies charge local competitors for leasing parts of their network.)”

Perhaps most relevant to its fight now against net neutrality, AT&T attempted to prioritize voice communications travelling over its wires, discriminating against data. This would have strangled the internet in its infancy. AT&T would have done so because – as Lawrence Lessig points out in The Future of Ideas, AT&T’s closed network of the early to mid-20th century was the exact opposite of the internet:

One network centralizes creativity; the other decentralizes it. One network is built to keep control of innovation; the other constitutionally renounces the right to control. One network closes itself except where permission is granted; the other dedicates itself to a commons.

How then was the internet able to develop when to be successful it required the wires and connections only AT&T could provide? How then was the freedom of the internet able to develop when it needed to utilize AT&T’s tightly controlled network? What entity was able to take on AT&T to force it to allow the most open market ever constructed to enter its closed system? Lessig explains, it was the government:

Beginning in 1968, when [the government] permitted foreign attachments to telephone wires, continuing through the 1970s, when it increasingly forced the Bells to lease lines to competitors, regardless of purpose, and ending in the 1980s with the breakup of AT&T, the government increasingly intervened to assure that this most powerful telecommunications company would not interfere with the emergence of competing data-communications companies.

Along every step of the way though, AT&T has fought and lobbied to get the government on its side and to manipulate the political process for the good of the company’s bottom line. Martin explained that one of the key people who has remained at the top level of AT&T during its many shake-ups has been Jim Cicconi, their top lobbyist:

When we were fighting off the Bells’ entry into long distance, Cicconi had a $60 million war chest, separate from his regular budget, for hiring political operatives around the country. He used the money to throw obstacles in the path of the Bells. He started and funded so-called “grassroots” organizations all over the place, astroturfing the countryside. His staffers searched out influential people who leaned in our direction and then funded their efforts on the issues that mattered to us. So, for example, Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Relief, received enough funding to set up special interest groups that have only a tangential connection to reforming the tax system. For example, the Media Freedom Project, which is a “project” of Americans for Tax Reform currently opposes net neutrality. As does another ATR “affiliate” The Property Rights Alliance. Similarly, the Alliance for Worker Freedom, another ATR affiliate, is opposed to another AT&T bugaboo, union card check. And of course, ATR is a member of the Internet Freedom Coalition, among other groups opposed to net neutrality. I’d be willing to bet that these groups still receive funding from Cicconi’s war chest. Of course, the other side does the same thing. Or at least that was Ciconni’s excuse when anyone challenged him on any of this stuff.

It seems AT&T is once again engaging in these tactics – as Matthew Lasar of Ars Technica reported yesterday:

AT&T Senior Vice President Jim Cicconi has sent out a e-mail to the company’s entire managerial staff urging them to deluge the FCC’s new discussion site with anti-net neutrality comments.

AT&T has a history of lobbying the government for any regulation or deregulation that best suits its interest. Its success is not that of a free market competitor who always had the best ideas (though it often has had good ideas), but of a savvy political operator who has thrown its weight around and manipulated public opinion, the political process, and regulators to undermine its competitors and strengthen its profits.

Now, they are funding groups opposed to government regulation and interference in the market – specifically on the matter of net neutrality. Adam D. Thierer, who wrote the article that provided most of the critical history I found of AT&T’s manipulation of the government to its own benefit, now works for The Progress and Freedom Foundation Project, whose main sponsor according to their website is AT&T. To my knowledge, it was Thierer who began the erroneous right wing talking point that net neutrality is a fairness doctrine for the internet which has now been repeated by Congresswoman Marsha Blackburn as well as on many, many right wing radio shows and blogs.

While AT&T claims to be promoting internet freedom by opposing network neutrality, it was only robust government regulation of AT&T that allowed the internet to develop at all. The freedom of the internet was not some natural occurrence – but the deliberate decision by the engineers at the Defense Department and then government regulators, oftentimes while stridently opposed by AT&T. The corporate libertarians such as Adam Thierer hired by AT&T to promote its agenda only seem to see government intervention impinging on freedom – rather than seeing that the power of a large corporation can be just as destructive. Of course, as Upton Sinclair said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!”

N.B. Neither Adam D. Thierer nor AT&T have responded to any attempts to contact them, though the post will be updated in the event that they do.

Update: Michael Balmoris of AT&T responded to my specific queries regarding net neutrality and AT&T’s fight against it with this vague pablum:

AT&T has long supported the principle of an open Internet and has conducted its business accordingly, and we support the FCC’s oversight of the wireline broadband market through case-by-case enforcement of the current four broadband principles. Furthermore, AT&T shares both President Obama’s and Chairman Genachowski’s vision of an open Internet—an Internet with a level playing field that benefits consumers and stimulates investment, innovation, and jobs.

[Image in the public domain.]

[reddit-me]I’ve started

[reddit-me]I’ve started  government regulation, and the blocking of financing to prevent the disruptive technology from taking off.

government regulation, and the blocking of financing to prevent the disruptive technology from taking off.