This is a busy season for me — but there should be some more substantive blog posts next week…

1. The Obama 20-somethings. Ashley Parker for the New York Times Magazine profiles “all the Obama 20-somethings” in an interesting profile of the new crowd in D.C. of smart, highly educated, highly motivated, civic-minded, young Obama staffers.

2. Lindsey Graham’s Cojones. You gotta hand it to Lindsey Graham — if nothing else, he’s got guts — from Dana Milbank of the Washington Post:

The lone pro-gun lawmaker to engage in the fight was the fearless Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), who rolled his eyes and shook his head when Lieberman got the NYPD’s Kelly to agree that the purchase of a gun could suggest that a terrorist “is about to go operational.”

“I’m not so sure this is the right solution,” Graham said, concerned that those on the terrorist watch list might be denied their Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms.

“If society decides that these people are too dangerous to get on an airplane with other people, then it’s probably appropriate to look very hard before you let them buy a gun,” countered Bloomberg.

“But we’re talking about a constitutional right here,” Graham went on. He then changed the subject, pretending the discussion was about a general ban on handguns. “The NRA — ” he began, then rephrased. “Some people believe banning handguns is the right answer to the gun violence problem. I’m not in that camp.”

Graham felt the need to assure the witnesses that he isn’t soft on terrorism: “I am all into national security. . . . Please understand that I feel differently not because I care less about terrorism.”

Jonathan Chait comments:

There’s a pretty hilarious double standard here about the rights of gun owners. Remember, Graham is one of the people who wants the government to be able to take anybody it believes has committed an act of terrorism, citizen or otherwise, and whisk them away to a military detention facility where they’ll have no rights whatsoever. No potential worries for government overreach or bureaucratic error there. But if you’re on the terrorist watch list, your right to own a gun remains inviolate, lest some innocent gun owner be trapped in a hellish star chamber world in which his fun purchase is slowed by legal delays.

3. Why Isn’t Fannie/Freddie Part of FinReg? Ezra Klein explains why regulation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac isn’t in the financial regulation bill.

4. Naive Conspiracy Theorists. William Saletan contributes to the whole epistemic closure debate with a guide on how not to be closed-minded politically, including this bit of advice:

Sanchez goes through a list of bogus or overhyped stories that have consumed Fox and the right-wing blogosphere: ACORN, Climategate, Obama’s supposed Muslim allegiance, and whether Bill Ayers wrote Obama’s memoir. Conservatives trapped in this feedback loop, he notes, become “far too willing to entertain all sorts of outlandish new ideas—provided they come from the universe of trusted sources.” When you think you’re being suspicious, you’re at your most gullible.

5. Saban. Connie Bruck in the New Yorker profiles Haim Saban, best known for bringing the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers to the United States — but who made much of his fortune licensing the rights to cartoon music internationally. As a side hobby, he tries to influence American foreign policy towards Israel. He doesn’t come off very well in the piece, but at least this one observation seems trenchant to me at first glance:

Saban pointed out that, in the late nineties, President Clinton had pushed Netanyahu very hard, but behind closed doors. “Bill Clinton somehow managed to be revered and adored by both the Palestinians and the Israelis,” he said. “Obama has managed to be looked at suspiciously by both. It’s not too late to fix that.”

6. The Obama=Socialism Canard. Jonathan Chait rather definitively deflates Jonah Goldberg’s faux-intellectual, Obama=socialism smear:

For almost all Republicans, the point of labeling Obama socialist is not to signal that he’s continuing the philosophical tradition of Roosevelt, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Carter and Clinton. The point is to signal the opposite: that Obama embodies a philosophy radically out of character with American history. Republicans have labeled Obama’s agenda as “socialism” because the term is widely conflated with Marxism, even though Goldberg concedes they are different things, and because “liberalism” is no longer a sufficiently scary term. Republicans endlessly called Bill Clinton a liberal, Al Gore a liberal — the term has lost some of its punch. So Obama must be something categorically different and vastly more frightening.

Goldberg is defending the tactic by arguing, in essence, that liberalism is a form of socialism, and Obama is a liberal, therefore he can be accurately called a socialist. But his esoteric exercise, intentionally or not, serves little function other than to dress up a smear in respectable intellectual attire. [my emphasis]

7. Imitating the Imitators of the Imitation. This Politico piece by Mike Allen and Kenneth P. Vogel explains how some elite Republicans are trying to set up a right wing equivalent of the left wing attempt to imitate the right wing’s media-think tank-political infrastructure:

Two organizers of the Republican groups even made pilgrimages earlier this year to pick the brain of John Podesta, the former Clinton White House chief of staff who, in 2003, founded the Center for American Progress and was a major proponent of Democrats developing the kind of infrastructure pioneered by Republicans.

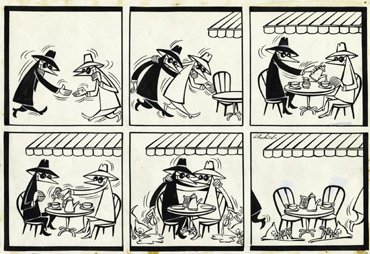

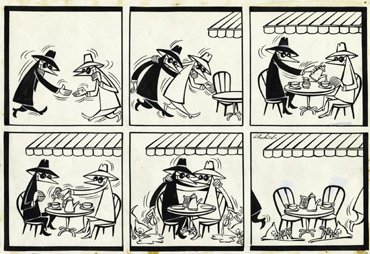

And of course, that right wing infrastructure was meant to imitate the left wing policy-media infrastructure of the left — the Brookings-New York Times axis. The whole imitation of imitation of imitation of imitation — spawning more and more organizations — reminds me a bit of those old Mad magazine comic strips:

8. The Underdog. Daniel Engber in Slate explores the underdog effect and various scientific studies of the underdog effect, including how it affects expectations:

The mere act of labeling one side as an underdog made the students think they were more likely to win.

9. Lost! Ed Martin in the Huffington Post is concerned with how the tv show Lost will end:

Not to put too much pressure on Lindelof and Cuse, but the future of broadcast television will to some extent be influenced by what you give us over these next few weeks.

10. Julián Castro. Zev Chafets of the New York Times Magazine profiles Julián Castro, mayor of San Antonio, Texas, and one of the up-and-coming Democrats. The article entirely elided his policy ideas or and barely mentioned his political temperament — but was interesting nevertheless.

[Image by me.]